Article related to the footage filmed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki

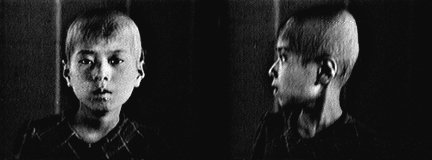

In My Lifetime uses footage from the documentary film The Effects of the Atomic Bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the only film shot immediately after the war, while the cities were still deserts of debris, the wounds were fresh, and the thousands suffering from radiation sickness were still alive. Here’s how historian Abe Mark Nornes describes the 22 minute film that was supressed for decades (original source link):

No critic has ever put The Effects of the Atomic Bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on their list of the greatest documentaries ever made, but this has something to do with how critics define greatness. It would mostly likely make the top of anyone’s list of films that people should see at least once in their lifetime—particularly if they come from a country

armed with nuclear weaponry. From a certain perspective, this is a mind-numbingly boring science film; from another, it is a horror film that leaves one speechless and trembling. Most filmmakers trying to represent events as extreme as the holocaust or the atomic bombings run up against the specter of the unprepresentable. The strange thing about this film is that the filmmakers never make this effort to begin with. They simply describe the two events in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the dry language of hard science. Nothing could be more unnerving. Another reason this film demands attention has to do with the circumstances of its production. Because of the unique situation in the wake of World War II, very few visual records of the atomic bombings were made. Despite the obvious historical importance of the attacks, information about the bombings was highly controlled for both security and for political reasons. This was the only instance when these weapons of mass destruction have been used against other humans, yet our moving image record of the incidents comes exclusively from this film project. If you have ever seen moving images showing the aftermath of atomic warfare—and most people in the world have—then they came from this film. The historical significance of the atomic bombings was not lost on Japanese filmmakers, who swiftly assembled teams to send to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They set out to create a documentary that would appeal to the world community to recognize the atomic attacks as atrocities. However, when American troops arrived in Nagasaki and stumbled upon one of the cameramen shooting amidst the rubble, they promptly arrested the man and confiscated his film. When they found out who he was working for, the Americans also halted the production itself. A power struggle ensued within the Occupation over the footage and the film, but eventually the Japanese filmmakers were allowed to finish their work. They produced one English-language film entitled The Effects of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This was the only film shot immediately after the war, while the cities were still plains of rubble, the wounds had yet to heal, and before the many thousands suffering from radiation sickness succumbed to their illnesses. Upon the film’s completion, the Japanese filmmakers were forced to pack up all the materials from the production process and send them to America. They did as ordered, very much against their will, but held back copies of the footage they had shot before the Americans’ arrival. They courageously hid these rolls of film in the false ceiling of the cinematographer’s studio, knowing that if they were caught with such top secret material they would be arrested and sent into exile in Okinawa. However, they were afraid that anything sent to America would be censored or “lost,” and humanity would never see the astounding scale of the suffering and destruction in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Their suspicions were not unfounded, although they were quite wrong about the Americans they were directly working with. The American filmmaker that managed the project and protected the Japanese filmmakers from other units in the Occupation was actually paving the way for a national release of the film through Warner Brothers in 1946, even going to far as to hold previews for the press. However, officials in Washington nixed these plans and the film came very close to entering the oblivion of suppression. We can thank that American filmmaker for saving the film, secreting away a 16mm print on a midwestern Air Force base (the original negative and production materials remain missing). And we can thank the efforts of the Japanese filmmakers for completing an astounding film that has served as humankind’s archive of atomic memories. Considering the nature of the film, its production, and the postwar relationship of America and Japan, it should be no surprise that the histories of this film are contentious and riddled with paranoia, assumptions and guesses—and all driven by postwar suspicion and complicated by a long-suppressed and still-incomplete archive. This small collection consists mostly of documentation from the film’s production saved by the American filmmaker, Daniel McGovern. It clears up many of the misunderstandings and mysteries surrounding the production of The Effects of the Atomic Bomb.For a close textual analysis of the film and a detailed historiography of the production and the controversies that have swirled around it ever since, please see the last chapter of my Japanese Documentary Film: the Meiji Era to Hiroshima (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003).—Abé Mark Nornes, Ann Arbor 2004

Scenario, The Effects of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (c1946) [Browse | pdf]

This is the English-language production script used by Lt. Daniel McGovern, who was the American in charge on the American side. McGovern was one of the cinematographers on The Memphis Belle(1944), and at the end of the war he made a visual record of the effectiveness of the air war in the Pacific theater for the Strategic Bombing Survey. He was among the first Americans to arrive in Japan, and immediately began filming the results of the strategic bombing of civilian targets in cities across Japan. He a large amount of film capturing daily life as well, a visual archive about living in the aftermath of the war of great historical and ethnographic value. McGovern also shot color footage of the atomic bombings alongside the Japanese filmmakers, who photographed exclusively in black and white. He added at least some of the handwritten comments on these pages after the war; a couple are also in my hand.

Four memos from a power struggle (December 24, 1945, etc.) [Page 1 | Page 2]

The four memos on these two pages constitute the paper trail for a little known power struggle over the atomic bomb film, a story which remains somewhat unclear to this day. Lt. McGovern of the Strategic Bombing Survey learned of the Japanese filmmakers’ project when he arrived in Japan to make a visual record of the American bombing campaign. Of course, the atomic bombings were of prime importance to the USSBS, and McGovern quickly recognized that the Japanese filmmakers had done a considerable amount of work that he did not want to reduplicate. At the same time, doctors at the Surgeon General’s office were documenting the effects of the atomic bombs on human bodies, and they too wanted the Japanese footage. In late 1945 and early 1946, McGovern and the Surgeon General’s office struggled for control over the film (that the medical effects sequences are a fraction of the entire film suggests that there were ulterior motives on the part of the Surgeon General’s office). These four memos capture a trace of the situation with the two offices at logger heads, but they do little to explain precisely what happened. The last memo, from the GHQ’s Walter Buck to the USSBS uses the controversial word “confiscate” (see discussion below), but it feels more like dry military lingo than a word signalling the pernicious intent assumed by the Japanese filmmakers and most postwar historians.

Memo, Lt. Daniel A. McGovern to Lt. Comdr. William P. Woodward (December 29, 1945) [Page 1| Page 2]

This is one of the memos McGovern wrote in support of the Japanese filmmakers. It is particularly helpful for establishing a timeline of events. McGovern is working the bureaucracy to procure the permissions and monies to support the Japanese filmmakers’ project. His trust in their ability to do the best job possible in completing the film is clear. The tone of this memo is in quite strong contrast to descriptions of cold, or even vicious, American attitudes in the histories of the atomic bomb film. Once again, note the matter-of-fact manner in which the word “confiscation” is used.

Memo, John Cook (January 3, 1946) [Page 1 | Page 2]

This memo records the gist of a meeting between the American principles, where it was finally agreed that the USSBS would complete the documentary and then send the film and production materials to the United States.

Procurement Demand (January 3, 1946) [Page 1 | Page 2]

This document was issued after the January 3 meeting in order to procure the funding to allow the Japanese crew to complete the film.

Memo, Capt. William Castles to Iwasaki Akira (January 11, 1945) [Page 1 | Page 2]

This is the infamous memo that informed the Japanese that their film and all the production materials would have to be packed into boxes and sent out of the country. Considering the subject matter, they assumed that the film would never see the light of a projector. The business-like, matter-of-fact language of the memorandum, combined with the fact that it is establishing a contractual relationship with Nippon Eigasha, suggests that the Japanese accounts of threats and intimidation are inflated by hard feelings or perhaps even paranoia.

Memo, Capt. G. S. Grimes to SCAP (January 17, 1946) [Page 1]

A memo indicating the production process agreed to, as well as the ultimate destination of the film.

Letter, Daniel A. McGovern to Akira Iwasaki (April 30, 1946) [Page 1]

One of the claims frequently made over the years was that the Japanese filmmakers’ work was basically stolen from them, “confiscated” in order to cover up the American’s horrifying atrocities in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The American in charge of the production at the Strategic Bombing Survey, Daniel A. McGovern, insisted that the Americans were simply taking what they had contractually paid Nippon Eigasha for. This memo lends credence to McGovern’s assertions, being the cover letter for a “receipt for service rendered.”

Statement of the Production Cost on “Effects of the Atomic Bomb,” signed by Iwasaki Akira (nd) [Page 1 | Page 2]

This is the bill for the film’s production, signed and submitted by producer Iwasaki Akira (one of the foremost film critics of the era, and a leader of the prewar proletarian film movement). The budget accounts for every stage of production, starting with the second trips for location shooting (the first were conducted before the U. S. military arrived on the main island). They even paid for the copy of the human effects sections produced for the Surgeon General’s office. It supports the American side’s claim that the relationship between the Japanese and Americans was contractual, and that the Japanese filmmakers were hired.

Receipt for Supply or Service (March 30, 1946) [Page 1 | Page 2]

McGovern’s boiler plate form is the final receipt for the services rendered by the Japanese filmmakers.

Memo, Lt. D. W. Davis to Lt. Daniel A. McGovern (March 30, 1946) [Page 1]

Another memo relating to the transfer of funds from the U. S. Government to Nippon Eigasha.

Memo, Daniel A. McGovern to Commanding General, Army Air Forces (July 10, 1946) [Page 1| Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5]

After returning to the United States, McGovern made several short documentaries about the strategic bombing campaigns. They drew on footage from the atomic bomb film, as well as color footage he shot himself, and were intended for use within the military. This memo, along with its attachment, also show that McGovern continued his discussions with Warner Brothers on other projects, even after his attempts to distribute the original film were squelched.

Memo, to Commanding General, Air University, Maxwell Field, Alabama (October 17, 1946) [Page 1]

A memo on the five films McGovern finally produced using footage culled from the USSBS project in Japan.

Memo, to Commanding General, Air University, Maxwell Field, Alabama (cApril 1947) [Page 1| Page 2 | Page 3]

A memo, and attachment, concerning the classification of the five films McGovern produced.

Letter, R. A. Winnecker to Erik Barnouw (June 27, 1968) [Page 1]

Winnecker was a historian in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense. Erik Barnouw was one of the first and finest scholars of the documentary, and the personal primarily responsible for bringing the world’s attention to this film. After obtaining a print of the film, and learning something of the history of the film’s suppression, Barnouw inquired about censorship and whether there were materials that the United States government retained. Winnecker responds quite correctly that the film in Barnouw’s possession had not been censored or recut. The letter reveals the depth of suspicion on the part of the scholar and his informants (one of whom was Iwasaki Akira), and also the utter lack of any institutional memory on the side of the government historian.